Imagine being a child in school, and you have no functional way to communicate what you need or want. You can’t read or write.

Imagine being a child in school, and you have no functional way to communicate what you need or want. You can’t read or write.

Maybe you are sad or mad. Maybe you’re tired, hungry or sick, but no one understands you when you try to express your feelings, and you don’t understand what it is that your teachers expect from you.

For many students on the autism spectrum, there are times at school and at home that feel like being somewhere no one speaks your language.

But for a group of Fayetteville-Manlius School District students with autism, their teachers and therapists have found a way to communicate with them more effectively through a language system made up of different types of visual supports.

Six years ago, Fayetteville-Manlius School District special education staff and administrators established a partnership with researchers from Boston Children’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School and Northeastern University to introduce a research-based, cutting-edge instructional methodology that uses state of the art technology and visual strategies to teach students diagnosed with autism and an accompanying communication disorder.

That partnership is still going strong and has expanded from one special education classroom with seven students at Mott Road Elementary School to include two additional classrooms: one at Fayetteville Elementary School and another at Wellwood Middle School. About 30 F-M students total are benefiting from the collaboration.

Visual Immersion System: A visual way to communicate

In the 2015-16 school year, Howard Shane, a Harvard Medical School Associate Professor and Director of the Center of Communication Enhancement at Boston’s Children’s Hospital, served as a consultant for F-M. It was while he conducted a student assessment at F-M that district staff first learned about Shane’s Visual Immersion System.

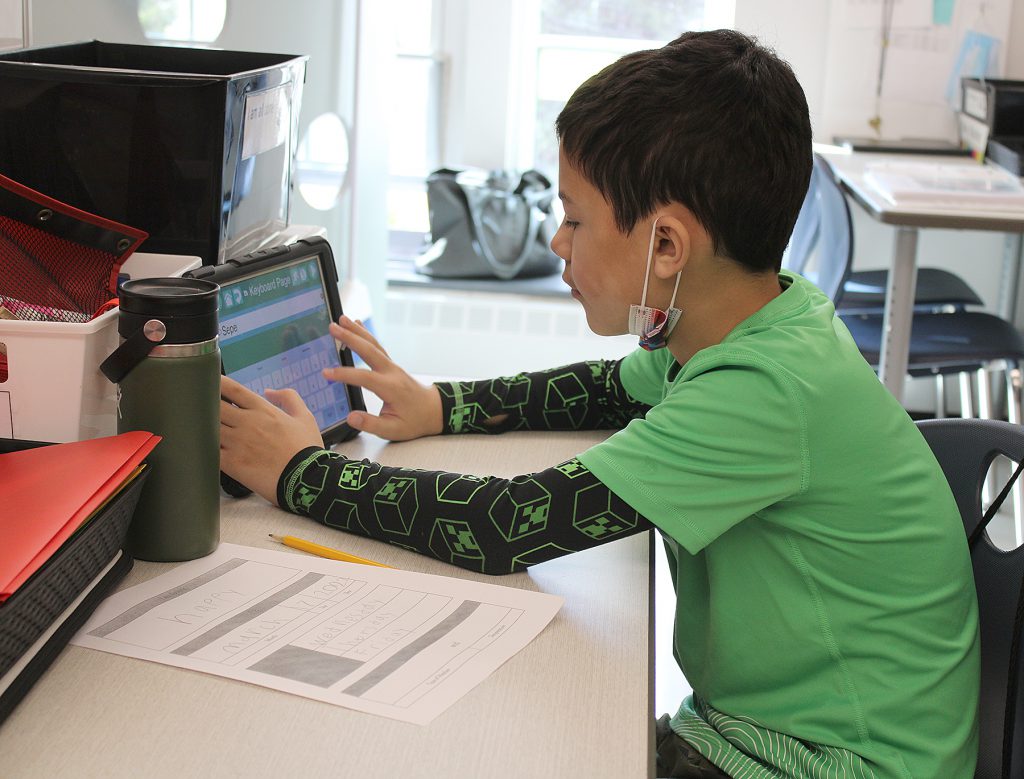

Visual Immersion System, or VIS, is a unique communication method that uses such visual supports as video clips, photographs and animation and other graphic symbols loaded into such devices as iPads and Apple watches to enhance and expand students’ language, learning and communication skills.

Visual Immersion System, or VIS, is a unique communication method that uses such visual supports as video clips, photographs and animation and other graphic symbols loaded into such devices as iPads and Apple watches to enhance and expand students’ language, learning and communication skills.

In simple terms, by watching targeted video clips, photos and animated graphics, the students are able to begin to better understand lessons, schedules and expectations. Over time, they use these visual cues to create novel sentences, sometimes visually with pictures or text and in some cases, spoken word. The primary goal is to have students advance to creating longer and more complex sentences.

VIS provides visual language instruction with a focus on seven communicative functions: requesting, following directives, commenting, answering questions, protesting/refusing, organization/transitions and social pragmatics. It provides a means for students with autism to more effectively communicate with, and understand, those around them.

After seeing VIS in action, F-M worked with Shane to provide VIS instruction during the 2016-17 school year to F-M’s entire special education staff. The following school year, the district formally partnered with Shane, along with Ralf Schlosser, a professor from Northeastern University, and other researchers, to bring VIS to a Mott Road Elementary School classroom of seven students diagnosed with autism who participated in a three-year research study that investigated the method’s efficacy.

Throughout the study, students’ parents were actively involved, including participating in focus groups, surveys and meetings with F-M staff and the researchers. The feedback they shared of how the program was affecting their children at home greatly enhanced the overall success of the program, Shane said. All parents reported improved overall communication while many even reported the development of spontaneous spoken language.

For the 2020-21 school year, the district expanded the program to a Wellwood Middle School special education classroom, essentially following the Mott Road students as they transitioned to middle school. The district has also established a VIS classroom at Fayetteville Elementary School, and a new VIS cohort began at Mott Road. The district is poised to expand VIS district wide over the next few years.

Shane, who still collaborates with the F-M educators, said the progress that the F-M students have made stems from the fact that the VIS takes advantage of the strong visual processing skills that are seen in children on the autism spectrum.

“But just as important to that success has been the commitment by the school district to provide the necessary tools and technology and the expertise of the incredibly talented staff who implemented the program,” Shane said. “To be honest, in all my years creating communication programs and approaches, I have never worked with a group as collectively dedicated to excellence and success as this F-M team.”

The power of VIS

When the COVID-19 pandemic halted in-person learning, the Mott Road students in the VIS three-year research project were finishing their last year in the study. Mott Road staff continued working with the students via remote instruction for the final two and half months of the school year, but it was more challenging than the face-to-face classroom experience.

As a result of the change from in-person to virtual instruction, the research team had to reduce the months of study in order to finalize its research.

“Although we were absolutely heartbroken shortening the time frame, our results showed substantial and continued student progress,” said Lisa Miori-Dinneen, F-M’s former assistant superintendent for special services who is working with the district as a consultant.

When the Mott Road students transitioned to Wellwood for fifth grade in 2020-21 and returned to mostly in-person learning, speech-language pathologist Andrea Benz transitioned with them. As she worked with and observed the VIS students in September 2020, she found that despite being home for the last few months of the 2019-20 school year with only remote instruction and no summer instruction, the students’ language and communication skills showed no regression.

When the Mott Road students transitioned to Wellwood for fifth grade in 2020-21 and returned to mostly in-person learning, speech-language pathologist Andrea Benz transitioned with them. As she worked with and observed the VIS students in September 2020, she found that despite being home for the last few months of the 2019-20 school year with only remote instruction and no summer instruction, the students’ language and communication skills showed no regression.

“Using VIS methodologies, students successfully transitioned to Wellwood, a brand new setting, able to make sense of their environment, understand teacher directions and follow classroom routines with success similar to that experienced at Mott Road pre-Covid,” Benz said.

Some of the students using VIS who were minimally speaking and unable to read or write have all shown improvement in each of those areas. They are now more effective at socially interacting with each other and their teachers. Their unique personalities are blossoming. One student is on track to transition in the next school year from a VIS classroom to a mix of general education and special education classes. He now plays an instrument and does much of his work independently without coaching from a teacher or teaching assistant.

“This demonstrates the power of the Visual Immersion System,” Miori-Dinneen said. “This definitely is a system that is proven effective. The kids are the proof.”

Sharing what they learned

Shane had been using VIS in clinical settings for more than 30 years before introducing it to F-M, which was the first school district in the nation to apply it and partner with Shane. Since their collaboration on the VIS research project, the F-M team of Benz, Miori-Dinneen, speech-language pathologist Jaqueline Cullen, special education teacher Lindsay O’Neill and director of instructional technology Laurel Chiesa, along with Shane, Schlosser and Anna Allen, have published three articles in professional research journals as well as co-written a chapter in a textbook that focuses on augmentative and alternative communication methods. They have also presented details of the research progress at professional conferences and shared their results with other educators.

The F-M group is in the process of creating a VIS guide in an electronically user-friendly format for educators and speech-language pathologists, including those at F-M and outside of the district.

“The VIS is the real deal and has proven to be a highly effective method to teach language and communication,” Miori-Dinneen said. “This is something that makes a substantial difference for children on the autism spectrum, and our hope is that anyone who wants to learn about it and apply it in their classroom will be able to do so.”